But what possessed the teenage you to try it in the first place?Įverett-Green: Ambition, probably, and vanity – motives that Proust spends a lot of time analyzing, and sending up.

Taylor: I remember that edition my dad had it in the bookcase. I ran aground pretty quickly, on a famously long sentence in the first chapter. I didn't actually read the novel until my 20s, and it took me almost a decade to get through it, but I persisted partly because of that initial reaction.Įverett-Green: I first tried reading Proust in my teens, in the old Chatto & Windus edition that sliced the novel into a dozen deceptively small volumes. For me, it was this remarkable moment where this distant genius spoke to me at the most personal level, "Hey, that happens to you too!" It was a moment I fictionalized in my novel, Mme Proust and the Kosher Kitchen – I was trying to talk about how we negotiate our relationship with towering historical figures. The smell of coal smoke always takes me back to holidays with my grandmother in Scotland. The thing was, I had had that experience too, the experience of sensory memory. We read only the famous passage in which the narrator dips the madeleine in his teacup and is transported back to his childhood holidays. Taylor: I was introduced to Proust in high-school French-lit class. Three Globe Arts writers, Robert Everett-Green, Rick Groen and Kate Taylor mark the centenary of Swann's Way by discussing how they started reading Proust and why they enjoyed In Search of Lost Time. The narrator's recovery of childhood memory through a cake dipped in tea has become a cultural touchstone the novel has been translated into numerous languages and adapted several times for film, and even as a graphic novel, in an ongoing project by French cartoonist Stéphane Heuet. Yet those who take the time often emerge committed enthusiasts. The novel's length – and the complexity of sentences that sometimes sprawl over an entire page – have given it the reputation of a daunting read. The complete work ran to more than a million words, describing in minute detail both the narrator's interior life and the society around him.

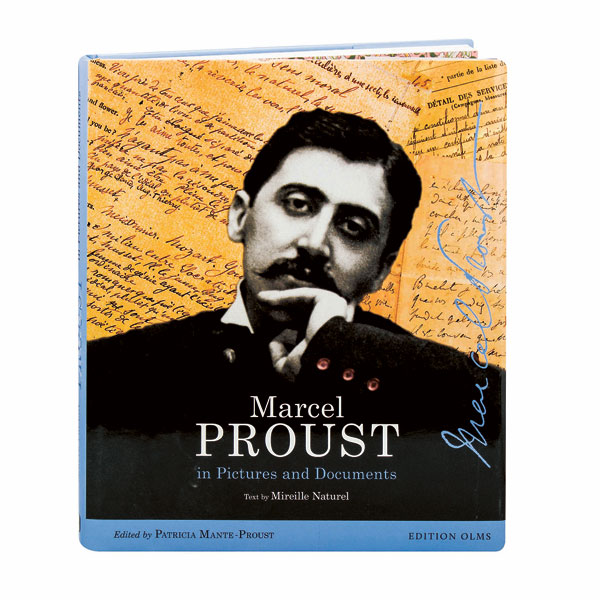

In November, 1913, the author paid for publication of Swann's Way himself the novelist André Gide, who was among those who had turned the book down, later told Proust he felt "a burning regret" for having rejected it.īy the time Proust died in 1922, Swann's Way was enshrined as the first, genre-changing instalment in Proust's seven-volume novel, In Search of Lost Time. One hundred years ago, French publishers were busy rejecting a wordy, novelistic treatise on childhood, memory and society by a Parisian dandy and dilettante named Marcel Proust.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)